The Nisqually Earthquake in 2001 changed the focus of Professor Philip Govedare’s paintings. He was at the College Art Association conference in Chicago during the earthquake. On television, he saw the historic brick building at 2nd Avenue and Jackson Street being used as an example of the structures that were badly damaged by the quake. His painting studio was in that building.

For many years, Govedare’s paintings had been essentially abstract, but he had been thinking about a return to working from nature. The temporary lack of a studio turned his musings into a reality. Govedare started with the Duwamish Waterway because, he says, “it was visually compelling, but also because it represented an interesting narrative of transformation. It was a site that had been dramatically altered through dredging, industry, and environmental degradation. Originally, it was a thriving ecosystem and rich fishing ground for the Duwamish tribe; today it is a highly toxic environment with extensive chemical contamination and has been designated a Superfund site.”

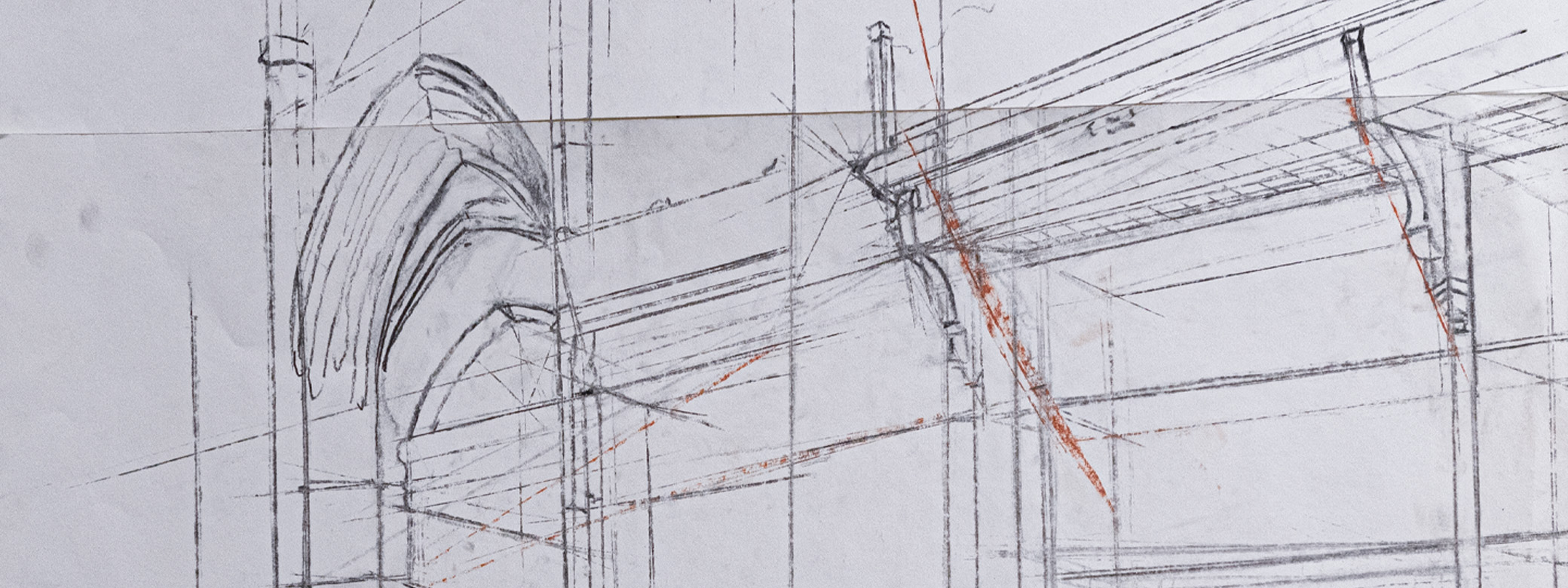

Govedare’s landscape interests have since shifted to the drier climates of high desert with color and light more closely resembling where he grew up in eastern Oregon. In January 2010, he was awarded a University of Washington Royalty Research Fund Scholar grant. His proposal was titled “Prehistoric and Post-Apocalyptic Landscape.” The grant allowed him to spend time in Utah soaking up two locales. Canyonlands National Park, which he describes as “dramatic, otherworldly, and monumental in scale and distance,” is largely untouched by humans, while the Bingham Canyon Mine is the largest open-pit copper mine in the world and the largest man-made canyon on earth (three-quarters of a mile deep and nearly three miles across). Govedare says, “The sheer scale of this reconfiguration of the land was of particular interest to me, as was the intricate and elaborate terracing and winding roads that come from the process of removing earth for mineral extraction.” After making numerous drawings of these landscapes, he returned to his studio to create paintings. With an aerial viewpoint and manipulated perspective, he created largely fictional and imaginary landscapes. He says, “This was a critical period for the development of my work.”

Govedare’s thinking about landscape, history, and our relationships to both affects how he approaches teaching. He says, “Something I want students to consider is the knowledge that we bring to our subject and how that influences the choices we make in terms of what we select and how we represent the world. For example, a landscape may be a depiction of a certain place, but what is our relationship individually and collectively to that place? What is its history? How do the conditions of atmosphere, light, temperature, smell and texture, provide a feeling for a place that is more than its description?” Govedare encourages his students in the Painting + Drawing Program to think about art in a broader context: “Art, and painting in particular, is in constant dialog with its past. But it also lives in a world that is very different than that which came before it. To be alive, art must come to terms with its unique moment in history.”