Rob Rhee and Dineo Seshee Bopape discuss the power of living materials, ongoing processes, and finding levels of acceptability as artists. This conversation was moderated by Daisy Nam on the occasion of Rhee’s exhibition Crossings at the Jacob Lawrence Gallery, University of Washington, in Seattle where he teaches. The text was lightly edited for length and clarity.

Daisy Nam (DN): Before we started to record, we were talking about how Dineo was at Skowhegan this summer as a faculty member and organizing dream workshops. Have either of you ever had a dream that helps you in your artwork?

Dineo Seshee Bopape (DSB): Yeah, several times. This week I had a dream of something being placed on my bed, and it reminded me of an idea of a work that I had in 2016 that I never got to realize. I couldn't travel with the thing in the car with me. It was too big to fit. That was the recent one. But in the past there've been songs that have come in dreams, and questions.

DN: What kind of questions?

DSB: About objects. Sometimes objects will present themselves, or even a cure or remedy for something that I could use inside a work, or something that needs to be explored.

Rob Rhee (RR): I've had recurring nightmares, but never recurring good dreams. But interestingly, I haven't had dreams that directly flow into the work. My sleep has been very inconsistent, so I wake up in the middle of the night, and I'm in between a waking and sleeping state. A lot of things show up, so I've kept a notebook to write them down, mostly practical solutions.

DN: You're trying to figure out the missing pieces in your sculpture and the dream fills in the blank?

RR: Or it's like a kind of different view of the piece. I can see it this way now.

DSB: I also sometimes get advice on how to practically solve a problem. Like, you must do your emails or buy coconut milk. Or today, go fix the car.

DN: Is that voice yours or is it someone else?

DSB: It feels like somebody else. I guess it is part of myself, but I always find that it's a little bit different from me, it's clearer.

RR: It's kind of a corny thing, but the etymology of inspiration in Latin is inspirati. It means to breathe and to breathe through. So it could be even a force, like wind, but it's like you've become a membrane or something you breathe through.

DN: Not corny at all! I met you two in 2010 when you were both at Columbia University getting your MFA. You were making sculptures and installations that stood out from the rest of the cohort because you were using living materials. I'm curious where that came from? What did you see elementally in the materials? Do you think there is knowledge embedded in material?

RR: We’ve never talked about this!

DSB: We were in Prentis Hall and our studios were opposite each other.

RR: That was meaningful for me.

DSB: For me too. I remember seeing you bringing in all these herbs and medicines into the studio. I used to just wonder about your studio.

RR: I had a mirror experience of you. I was certainly curious about the materials, but I didn't think of them elementally. That came from seeing your work, Dineo, and seeing the way you think about things.

I think it started with one clear narrative: I wanted to make this child-sized suit of armor. I started using eggplant skins to get this leathery substance. At the time, Takashi Murakami was doing those Louis Vuitton bags, and I didn't want to have a conversation about Louis Vuitton. I wanted to have a conversation about this child-sized suit of armor that I saw at the Met, and inheritance. This suit of armor came from France or Spain, from a failed inheritance. The balance of power in Europe was thrown off by this child being born to two different families, and so instead of getting the literal inheritance, he got this figurative inheritance in the suit of armor.

I thought about my own connection to Korea and being second generation and having inheritances that I don't have actual connection to. I felt drawn to this suit of armor when I saw it. When things reach out to you, it's never by accident. It's not that this suit of armor is objectively the best artifact, but there was something calling to me and I listened. Then seeing the way Dineo is thinking about personal history, collective history, national history, the metaphysical, and the material. When I think about how you would talk about iron in the soil, I’m asking, what is that connection, what is the mechanism, and how are those things communicated so the connection is believed to exist? That's something I saw just being next to your studio. It kind of came through the walls.

DSB: When you talk about the armor, what comes up for me is Salman Rushdie’s novel Midnight’s Children. It’s about these two women who give birth on the same night and their babies get swapped. They are from different classes and it’s also the time of the partition between Pakistan and India. What it means for those boys to grow up in that context and the complications embedded in their birth. I started to play around with my artist’s bio at Columbia. I found out that’s when this book was published in 1981, the year I was born.

When I was at Columbia, I actually wasn’t working with natural materials—going back to your initial question, Daisy. I was using lots of industrial materials, or plastic that looked like wood, or glitter. But then I went to Norway, and visited a lake at sunset. I noticed the water glistening from the sun, and that was glitter! I was thinking that I've been wanting this water all this time. I was drawn to glitter because of how water glistens when the sun hits it. I was trying to capture that, but glitter was the language I was using.

DN: You found the origin of your material search.

DSB: Perhaps it was a kind of knowing of the natural materials. I was using plastic plants, but I was still longing for the real thing.

RR: That makes me think of the farm. I'm growing gourds there, and just by happenstance, I laid down this landscape fabric, which was from someone's previous use of the plot. It has all these letter-number names for each plant location: E 11, E 12, and so on. But when I was keeping track of my plants using those names, I realized that that was a kind of broader phenomenon––this idea that I'm using someone else's name for the thing in front of me.

There is this simultaneous closeness and distance that's just always a part of experience. I feel like that's something about the visceral or just that idea of glitter. I love that we use the name to get us close to the thing, but then when we have the phenomenal experience, the name takes a backseat. Maybe there is a respect for that phenomenal experience.

DSB: Yeah, I'm reminded of this healer from Zimbabwe. He doesn't know the names of plants. He just knows that this one and that one work together. In any land he goes to, he can connect to the plants. But he doesn't know the names, he doesn't care about the names, it's the magic of it all.

It’s about scratching away at this thing and not knowing it, not even having the language for it. Sometimes you make a work without knowing what it will be about; you just have an intuitive following of a direction and this thing reveals itself. Maybe I become more in tune with it, or awakened. I don't know what the process is, or the words to call the process, but a ripening or something that wasn't clear before in the experience of that.

DN: In your work, you’re both combining multiple objects. The sculptures are never made from a singular material that forms a singular sculpture. Does your intuition come into play during the process of putting objects together? Almost like the herbalist, just knowing what two plants need to be together?

DSB: Perhaps it’s the first ingredient that starts it off. Maybe it’s first a piece of glass then afterwards it needs to be tied to a string.

DN: Do you intuitively know when all those things come together and you’ve completed the work?

RR: I've definitely repurposed sculptures into other works multiple times. I know when something's arrived, but then I've also taken something that's supposedly arrived or that's felt like it's arrived, and started it back in the cycle. Then I get really neurotic, and think to myself, “Is this about death or failure? Is this about rebirth or life?” Does that happen for you, Dineo?

DSB: At Skowhegan I made this fresco. There were times in the making where I thought, okay, this could be acceptable for myself. I could accept the work. But then I kept going. I was like, no, let me do this, let me try this. I made a move, and then that move required that I make another move, but then I needed to go to the airport! In the end, I didn't have enough time.

RR: I feel like there's so much when you said this is acceptable to me. That felt so succinct and so true about the terms of the work.

DN: There must be so much pressure when you're trying to finish work for an exhibition, it can probably feel forced to have this looming deadline for something to be on view.

DBS: Although sometimes the thing that the work needs might be a mistake, they also bring their own spice. I had a show at Migros Museum of Contemporary Art in Zürich, and the technical team made a mistake for one of the earthen structures, but it was such a great mistake. The walls were supposed to be a certain height, and the diameter was supposed to be a certain length. We ended up cutting the wall to make two pieces out of it, that became a table, and the other part became a shorter wall. The interaction between the original two walls was also more interesting. That was a great disturbance. Rob, do you ever push the limits of what is acceptable to yourself for the work?

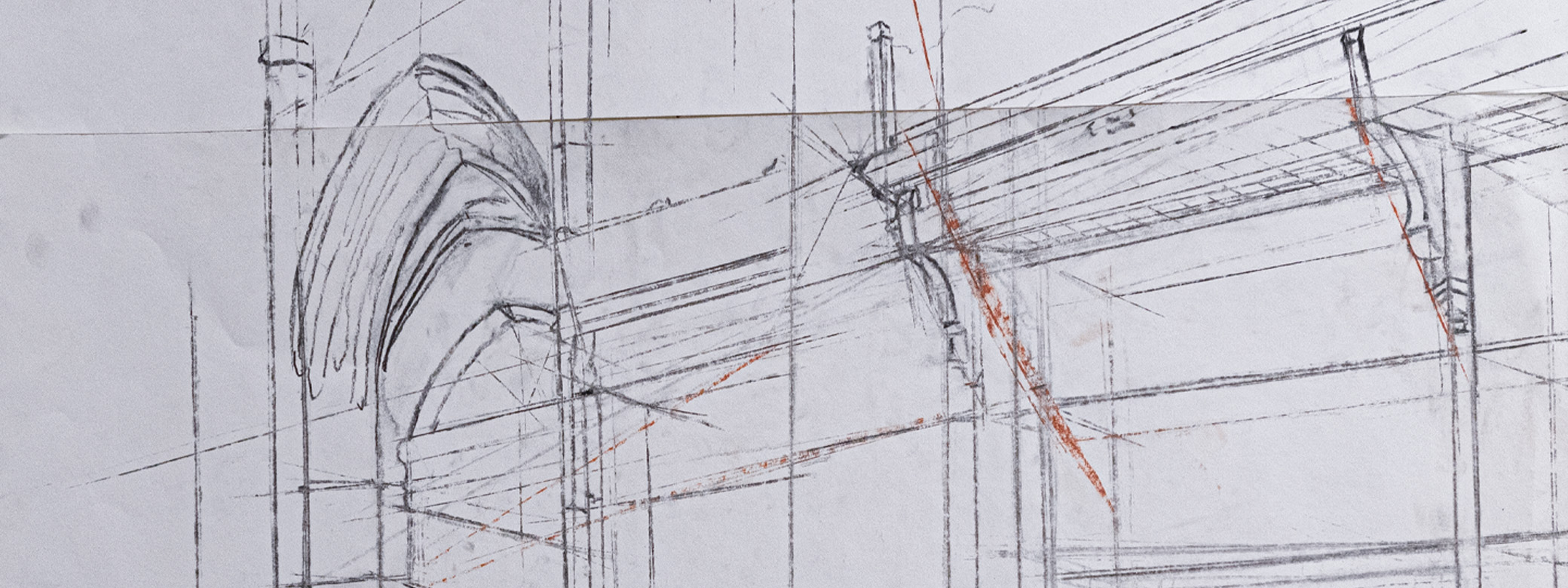

RR: For this show I'm putting up, I'm having to make things quicker than I've felt comfortable with recently. I’m excited about having things happen in this show that just feel unknown and surprising and scary. There were things that I envisioned, and things that I also watched unfold, and some I'm just observing as base-level phenomena stuff. It’s almost like the dreaming we were talking about in the beginning. I think it's a continuum of seeing things happen, versus envisioning them, versus being seen by the work.

The thought of “this feels acceptable to me,” it's like doing intuition, the body, the bruise, doing work on yourself and doing work in the work. They're all connected because when I feel shame, that's my own stuff. I've definitely had experiences where I've talked the work into existence and then felt a lot of shame about that.

DN: Like it’s not authentic or something?

RR: Exactly. And it’s not even bad. Sometimes you get into making a thing, you act as if you want it to be there, but then it isn't really there yet. There's one piece in the show that I worked on a long time. I'm like, I know who you are, I feel like it. I know what's going on.

DSB: I understand that. Several years back, I had a work in Helsinki. I was imagining a billboard, which is very specific and not usually how I work. But it didn't quite read like that. I was disappointed in the new form it had taken. Then the people helping to produce the work were telling me about their daughter who had Down syndrome, whom they had considered aborting but didn’t. They were telling me so many joyous stories about this now-woman, she's living on her own and thriving. It made me think differently about the work.

I perhaps had shame as well. Was it me and my shame and this object, and how to then accept the new thing? It’s not a mistake, but it's its own thing that is introducing other things to me and to the world as well, and how to live with it. Just the story of that family made me think differently around things that are things, situations that are acceptable or not acceptable to me or to others. I hardly ever think about the audience when making work. It's always just for myself that I have to be satisfied with it more than trying to get somebody else to understand it, if they will, or whoever needs to understand it will; who doesn't, it's not for them perhaps.

RR: I didn’t know then when I started working with the gourds, but it's something that I really have come to appreciate based on who I am and how I operate in the world. With the gourds, I can't speed them up. I can't change the way they work. So it became a process. The seeds get planted in June, and then they go outside in July, and then the fruits come out in August and you cut the fruits in September, and then it takes a couple months to draw, and then you need to wash them. I can't switch July for September, for example.

That phrase “acceptable to me” really hit. I've been very grateful for processes which allow me to not have to say yes or no. This is the way it is and I can't speed this up or change this. How do I give space to figuring out whether or not this is acceptable to me? And where does acceptability come from? Is it the institution, the process, the curatorial relationships, viewers? What sustains you? The questions are scary sometimes. Those are intense moments of feeling. It is not like they're coming all the time. They're shades of feeling.

DN: You're both working with living material whether it’s gourds, plants, or soil. I think of other sculptural materials like marble, that’s hard. It's been dead. It is from the earth, but it's been in its form for a very long time. I’m curious about your thoughts on what makes a sculpture alive. I was talking to another sculptor Michelle Lopez and she was sharing an idea of sculpture as sleeping that then awakens, and how to create that dynamic. Is it the audience that awakens it? There are all these colonial monuments that have no energy, feeling of aliveness, that seem dead as objects. Yet because of their publicness, they are seen by millions of people.

DSB: I've never considered whether marble sculptures are also alive or not. The mountain is alive and the rocks are. I never considered Michaelangelo sculptures to be alive or not, beyond the shape that they're in. But yeah, materials as still singing. Perhaps it's that thing about the two ingredients coming together that causes a spark and makes that thing alive, or it makes other conversations more visible or more audible and present.

RR: It reminds me of the Confucian “as if” ritual of caring for your deceased family members by laying out food for them. The question of whether or not your ancestors are alive and actually eating the food is less important than whether or not we act as if they are alive. The ritual brings them to life. The idea of the alive or dead sculpture, or sleeping sculpture, is bound to that idea. Does that as if experience arrive with the work? I do think you can create those as if moments where stone becomes alive or an ancestor is present.

DSB: That makes me wonder about when receiving, when breathed into, when inspired to action, and the act of putting materials in relationship to each other. Does the as if exists before in the gathering of those materials together. Or, are these two things really more than they are, or present in a different way than they usually are, and being totally embodied into that as if.

I'm curious about what you said about the old sculptures being dead. What came to mind was an energy around them, not themselves being dead but they give off or produce this dead energy around them. I'm reminded of the “Fees Must Fall” and “Rhoades Must Fall” protests at the University of Cape Town. One student went with a bucket of feces and poured it over the colonial sculpture because the sculpture was too alive, or what it represented was too alive, white supremacy. So they exude something or they activate things still. They are instrumental.

DN: Wow, a bucket of shit neutralized that instrument in an instant!

DSB: It’s a good intervention. Also what it did affected the world. The protests went to the UK, the US, and other places with colonial statues. It was a ripple. The bucket of feces from the Cape of Good Hope!

RR: Incredible. In JADAM, a Korean method of organic farming, one type of fertilizer can be made from human feces. It takes the longest to ferment and cure. I love the idea of the neutralizing act, as opposed to defacement, that brings life and all of its experiences to the thing that exudes death. That's a really inspired act.

DSB: Rob, I just had a memory of your studio again, of all that material—the herbs and organic spices—waiting and breathing together, not in the market and not in a home but in an in-between space where something else was brewing.