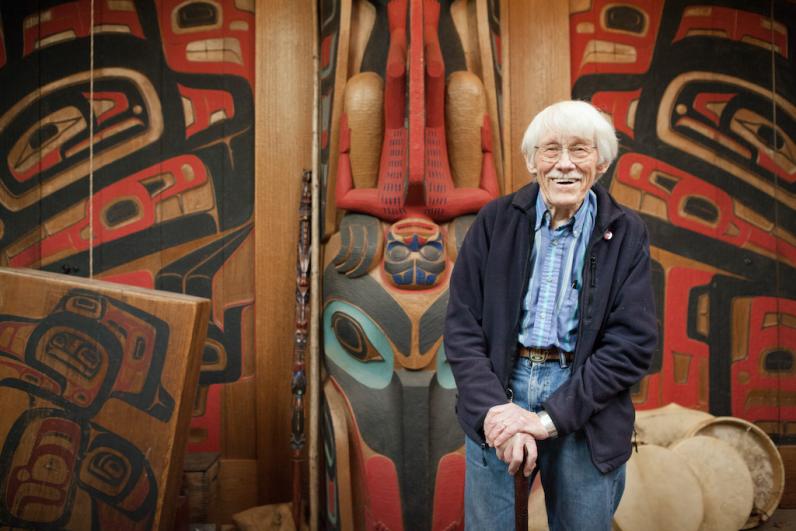

The School of Art + Art History + Design is sad to announce the passing of Professor Emeritus Bill Holm on December 16, 2020. He died at home in his sleep at the age of 95.

Brief Biography

Holm was born in Montana, and his family moved to Seattle when he was twelve. Shortly after that, he met Dr. Erna Gunther, director of the Washington State Museum. She helped to grow his already deep interest in Native peoples and their cultures.

After serving in World War II, Holm attended the University of Washington on the GI Bill. He received a BA in Art (painting) in 1949 and an MFA in painting in 1951. Holm later returned for two teaching certificates. He taught art at Lincoln High School in Seattle in the 1950s and 1960s. After publication of his influential book Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form (UW Press, 1965), Holm was recruited in 1968 to start teaching in the School of Art and working at the Burke Museum. His classes on Northwest Coast Native art were legendary, and he continued teaching them until his retirement in 1985.

Remembrances

Robin K. Wright

As with many people, I can say that Bill Holm profoundly changed my life. From the first day I attended Bill’s ART H 333 class (the second year he taught it) as a directionless undergraduate humanities major, it was like being sucked down a rabbit hole into a new world of visual delights and cultural meanings. I found the joy of learning imparted by the infectious joy Bill expressed in teaching about Northwest Coast art and culture. He literally jumped around. Perhaps most effectively, he taught the art of seeing the logic of lines and shapes by forcing students to attempt to draw them. This was not done to turn students into artists, but rather to use the hand to train the eyes to see what they were missing without the experience of trying it themselves. The simple quiz to place a cheek design in the vacant corner of a mouth was literally an "eye-ovoid" opener.

From teaching an understanding of two-dimensional design, Bill moved on to sculpture in ART H 334. Differences in tribal styles became apparent, and objects that had been simply “Northwest Coast” took on subtle yet distinguishable differences created through time and space, while the characteristic evidence of artists’ hands emerged. He did not encourage his students to try carving, but I still have a crooked little finger from a severed tendon acquired when I attempted to carve a Haida-style beaver (to be clear, this happened in the summer in Minnesota, not during class).

By the time spring quarter came, we moved on to ART H 335. This class taught us how the physical things we had been learning about were not just “objects of art” but were alive and functioned in an intangible ceremonial world of living cultures, a world that had been attacked by a dominating colonial world that made the art and the ceremony that validated it illegal. From the moment that potlatching was no longer illegal and dancing was once again done publicly in bighouses (1953), Bill and Marty were invited to attend. In 1980, as a young graduate student, I was able to attend, masquerading as one of Bill’s family, the opening potlatch of the U’mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay, to celebrate the return of the confiscated potlatch regalia that had been taken by the government at Dan Cranmer’s “illegal” 1921 Christmas potlatch. That same year, I attended Robert Davidson’s potlatch in Old Massett on Haida Gwaii, shortly after I finished my master’s thesis on Haida argillite pipes, again with the Holm family. Thirty-six years later, as invited guests, my spouse, Carol Ivory, and I accompanied Bill and Marty Holm to a potlatch in Skidegate, Haida Gwaii, for the installation of Guujaaw as the new Chief Gidansda. Bill Holm was the only non-Native person to receive one of the twenty-five coppers gifted to honored invited chiefs.

I believe I sat in on nearly every class Bill taught from 1969 until I graduated with a PhD in art history in 1985, the same spring that he retired. I was honored to step into his oversized academic shoes and continued to learn from him throughout his life. I hope that the opportunities offered by the Bill Holm Center for the Study of Northwest Coast Native Art will inspire others, as he inspired me.

— Robin K. Wright is Professor Emerita of Art History in the School of Art + Art History + Design and Curator Emerita at the Burke Museum. She founded the Bill Holm Center at the Burke Museum in 2004.

Martha Kingsbury

It was wonderful to have Bill Holm on the art history faculty — always modest and soft spoken in demeanor while so innovative and wide ranging in his work. He brought new points of view and strategies to art history. I remember vividly the excitement among us as Bill Holm, with George Quimby, concluded reconstruction from film fragments of “In the Land of the Headhunters.” Famed photographer Edward S. Curtis had made the film back in 1914 in collaboration with British Columbia Kwakwaka’wakw people, as a wildly exciting and exotic narrative full of realities and inventions both. Renamed “In the Land of the War Canoes” in 1973, now we were shown how to value it as neither a narrative nor a documentary but a historical collaboration between two dramatic traditions — a particularly rich Native North American ceremonialism and the newly emerging genre of American cinema. It was marvelous!

— Martha Kingsbury is Professor Emerita of Art History in the School of Art + Art History + Design.

Barbara Brotherton

Forty years ago, when I was visiting the Northwest, I met Bill Holm who said “come attend my classes.” I was a student at the University of California studying European art history but had come under the spell of Northwest Coast Native art. That interaction forever changed my life. From his office at the Burke Museum, Bill was creating a platform for what would later be called the “new art history,” an approach to studying art forms outside of the “western canon” using methodologies that were inclusive of Native histories. Bill wasn’t trying to start a revolution but he was bringing new questions and analysis to his comprehensive study of Northwest Coast Native art. His seminal book, Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form, first published in 1965, put the distinctive forms of the art into visual perspective. Yet Bill built upon the stylistic examination by revealing the individuality of particular artists, like Charles Edensaw and Willie Seaweed, and by coupling those inquiries with knowledge gained from personal relationships and cultural involvement. Although others inscribed him as “the expert” Bill understood that true understanding of the art resided within the Native community and the ongoing practice of art and ceremony.

Bill created a Native art history program with advanced degrees at UW, one of only three in the entire U.S. at the time. The UW School of Art and the Burke museum became the locus for students, collectors, museum professionals, and Native artists who, under Bill’s guidance, created projects that put Indigenous art history in the mainstream.

Bill Holm was a humble man yet one of incredible stature. He had deep respect for Native people and their traditions and understood that the art was inextricably connected to real people, past and present. He was an amazing teacher as his packed classes in Kane Hall were testament. When the lights went down and the slide images came up, the magic began. His vast knowledge and deep sensitivity brought Indigenous art to the level of other great art traditions. In the pre-digital days, Bill created a rare archive of images, taken by him in museum storerooms across the world. He had even rarer images of ceremonial dancing and oratory taken at potlatches, which he used to bring the art to life in the lectures. This slide archive was kept in his office alongside a slide duplicator for students and artists to use. Much learning and conversation occurred around those slide binders! Bill was one of the most generous people I have ever known, freely sharing his ideas and resources. This largesse, devoid of the knowledge-hoarding that can occur in the academy, laid the foundation for a respectful and collaborative practice that continues today.

— Barbara Brotherton is the Curator of Native American Art at Seattle Art Museum.

Jeanette Mills

I grew up in Seattle but had only minimal knowledge about the Native cultures and art of this region. When I took my first class with Bill Holm in 1982, my eyes were opened, and I was hooked. Bill's enthusiasm for the subject of Northwest Coast Native art and for teaching was boundless. It was also infectious. I spent over two decades sharing what I'd learned from him in talks at retirement communities, adult continuing education classes, and as a lecturer on Inside Passage cruise ships.

Bill was never much interested in small talk, but ask him a question about Northwest Coast Native art and culture (or many other topics) and a conversation was started that could range far and wide. His knowledge was encyclopedic, and he was always willing to share it. One such conversation with him led me to my thesis topic when I was working on an MA in Anthropology specializing in Museology, and I benefited from having him as one of my thesis advisors.

I am so thankful that I met Bill in 1982 and that I was able to stay in contact with him over the years since then. He enriched my life as he did with so many other people.

— Jeanette Mills is a 30-year staff member in the UW School of Art + Art History + Design.

Memorial Gifts

Memorial gifts to the Bill Holm Center for the Study of Northwest Coast Native Art may be sent to the Burke Museum at Box 353010, Seattle, WA 98195-3010 or donate online. Memorial gifts may also be made to Camp Nor’wester at PO Box 1055, Edmonds, WA 98020 or donate online.

Links

- "Bill Holm, a giant of Native Northwest Coast art, dies at 95." Seattle Times, December 24, 2020.

- "Bill Holm (1925-2020)." HistoryLink, May 26, 2013, updated December 27, 2020.

- Obituary written by family and colleagues (PDF; includes a list of his books).

- "Remembering Bill Holm's respectful cultural support." Seattle Times, January 5, 2021.

- "In Memoriam — Bill Holm, 1925–2020." Preview, February–March 2021.

- "Master Mentor." University of Washington Magazine, Spring 2021 (PDF, go to page 66).

- "Bill Holm—In Memoriam." Burke Museum website, March 22, 2021.