Known for his provocative interventions into Western European and American art history, Kent Monkman explores themes of colonization, sexuality, loss, and resilience. Across painting, film/video, performance, and installation, his work represents the complexities of historic and contemporary Indigenous experiences and provides audiences with opportunities to reflect on the unique power of images for understanding history.

Nominated by faculty in the Division of Art History at the University of Washington School of Art + Art History + Design, Kent Monkman is one of the three guests for the Spring 2023’s UW Public Lecture Series by the Graduate School. Monkman’s lecture Miss Chief in the Museum is on April 19, 2023, and is co-sponsored by the Division of Art History and other units. In honor of his upcoming visit to the Seattle campus, four faculty in the Division of Art History’s geographically and methodologically diverse Art of the Americas cluster and a first-year doctoral student reflect on Monkman’s artwork and how it’s challenging the collective understanding of American art history.

Caitlin Earley, Assistant Professor of Art History, Art of the Ancient Americas

If you’ve learned any sort of traditional American history or art history (I’m thinking of manifest destiny, the Hudson River school, or ideas about the “unspoiled wilderness” of the American west) Monkman’s work turns it on its head. His paintings and performances incorporate and insist on Indigenous understandings of people and the landscape. He asks us to question what American art is, how it has been codified and taught, and what the future of American art might look like. At the same time, Monkman’s work poses vital questions about the study of ancient Indigenous art, asking us to reckon with the biases, inequities, and assumptions inherent in the collection and interpretation of art of the Americas.

Jennifer Baez, Assistant Professor of Art History, Art of Colonial Latin America and the African Diaspora

Monkman’s work draws on pictorial tropes and grand narratives about Native life that stem primarily from Romanticism. Yet his work also engages some of the most nagging philosophical questions that were foundational to art history as a field. He grapples with periodization itself, a system of categorizing art into neat periods that is useful for comparing things, but problematic because it distorts the historical process. Monkman highlights and parodies the artificiality and false neutrality of these constructed lenses. His work asks us to question why museums defer to colonial representations of the American Indian, and why we are satisfied with settler accounts despite the colonial period being relatively short in comparison to Native Americans’ long history of inhabiting this land. Monkman problematizes these principles, warping time yet insisting on historical specificity, narrativizing the interruptions of history while imagining Indigenous futurities.

Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, Associate Professor of Art History, Northwest Native Art

Monkman holds a mirror up to art history, thereby reflecting the colonial histories that erased First Peoples from the North American landscape. Through absorbing and reframing the lens of many settler artists, including George Catlin and Albert Bierstadt, Monkman challenges common understandings of American history. His works explore themes of gender and colonized sexuality while taking inspiration from the form of the Old Masters, such as Eugène Delacroix and Peter Paul Rubens. His monumental paintings bring us to new understandings of what a “history painting” is and who gets to decide, all the while honoring Indigenous experience and resilience.

Mariah Ribeiro, PhD Candidate, Art History

What intrigues me as a scholar of Modern and Contemporary Native art is how Kent Monkman often eschews the visual rhetoric of many of his contemporaries—namely conceptualism—in favor of the history painting, a mode of representation deeply rooted in Europe and its colonial history.

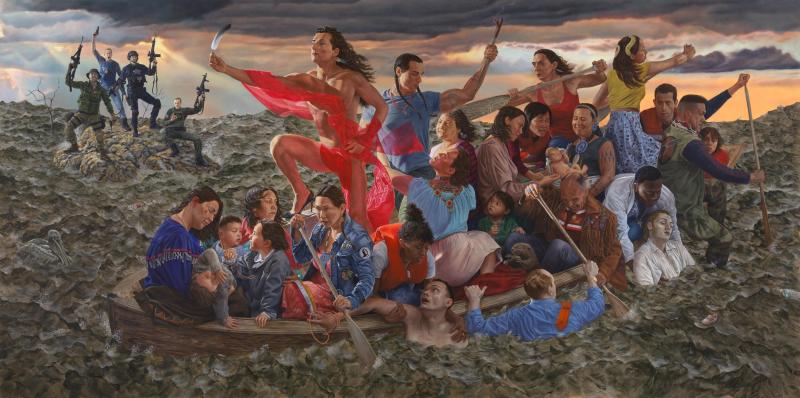

What intrigues me as a scholar of Modern and Contemporary Native art is how Kent Monkman often eschews the visual rhetoric of many of his contemporaries—namely conceptualism—in favor of the history painting, a mode of representation deeply rooted in Europe and its colonial history. In much of his art, from his insertion of queer/two-spirit tableaus into Hudson River School landscapes to his lampooning of Primitivism in Casualties of Modernity (2015), Monkman’s playful and biting humor subverts and inverts the signifiers of colonialism, patriarchy, and heteronormativity embedded in the Western art canon. But this humor and playfulness often drop away in his history paintings, a genre of painting closely aligned with European power and authority, allowing Monkman to instead center the emotional immediacy and weight of the stories he is representing. In paintings like The Scream (2017) or They Are Warriors (2017), which depict the Sixties Scoop and the violence against Water Protectors at Standing Rock respectively, Monkman doesn’t just reverse the colonial gaze, but quite literally appropriates the “master’s tools.” By doing so, Monkman assumes the role of a contemporary “Old Master,” conveying and authorizing Indigenous experiences and perspectives into a history that has long sought to erase them completely.

Juliet Sperling, Assistant Professor of Art History, American Art

If we look at his 2019 painting mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People): Resurgence of the People alongside the other artworks that refigure the same source material, we can see why this approach is so popular and powerful in American art history. mistikôsiwak riffs on a canonical 1851 history painting, George Washington Crossing the Delaware, that was created to project a certain myth of American identity and values.

Kent Monkman's work contributes to an ongoing collective effort among contemporary artists to refigure history: that is, to intentionally expose, challenge, reclaim, or otherwise contend with art historical legacies of representing race and difference. If we look at his 2019 painting mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People): Resurgence of the People alongside the other artworks that refigure the same source material, we can see why this approach is so popular and powerful in American art history. mistikôsiwak riffs on a canonical 1851 history painting, George Washington Crossing the Delaware, that was created to project a certain myth of American identity and values. Monkman makes changes to the original composition that ask the viewer to question those influential ideas about our nation, its citizens, its physical and political borders, its future--and importantly, to do so in different ways than other reinterpretations of the original painting by artists Jacob Lawrence, Robert Colescott, Roger Shimomura, and Kara Walker. By placing his work in conversation with other contemporary artists who are rethinking these formative legacies, Monkman shows us that art history is not just about the past, it's about the future.