Professor Emerita, Art History

Fields of Interest

Education

Biography

Estelle Lingo's expertise is Early Modern European Art. She offered graduate and undergraduate courses in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European art and taught regularly at the UW’s Rome Center. Lingo retired in 2025.

I am a specialist in early modern European art with research interests that range from the sixteenth century to the present and engage questions of historical visualities, non-textual knowledge, canon formation, media specificity, periodization, gender, and the historiography of Western art history. Through fine-grained historical research, I seek to recover the cultural specificity of what is commonly called “style” and to activate visual forms as primary sources with the potential to reconfigure larger scholarly narratives in and beyond art history. My scholarship reorients our understanding of the formation of the ideal of Greek classicism, the historical stakes of the “baroque” in sculpture, and, in my most recent work on Caravaggio and the pan-European movement he inspired, Western concepts of naturalism and virtuality. My research has been supported by fellowships from Villa I Tatti, CASVA, and the Kress Foundation, and from 2016-18 I was the Andrew W. Mellon Professor at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery in Washington.

My current book project, To Destroy Caravaggio: Art History and the Western Tradition, interrogates the repeated assertions of seventeenth-century art writers that Caravaggio “had come into the world to destroy painting.” My study argues that academic art theory took shape around the perceived necessity of repressing Caravaggio’s innovative technique and the new form of visuality it enabled. This same academic criticism actively produced key conceptual binaries—including “naturalism” and “idealism”—upon which the self-narration of the Western artistic tradition long relied. These conceptual categories, moreover, structured the academic discipline of art history from its emergence in the nineteenth century. My book will offer a new account of Caravaggism as a technique that, in contrast to the projective methods of linear perspective, was fundamentally receptive and approached the studio model from the scenario of still life. Organized around the ground-zero moments of c. 1600 and c. 1900, my study proposes that far from a teleological and technological progression from linear perspective to photography, post-Renaissance image-making in the West was shaped by fear of and resistance to what I term “the photographic option.” By activating censured artworks to interrogate the very categories used against them, we obtain a new vantage point on the investments of the Western tradition, a vantage point critical to the urgent work now underway of rethinking the practice of art history within a global framework.

-

Selected Research

- “Passeri’s Prologue, the Paragone, and the Hardness of Sculpture’s Perfection,” in Perfection: The Evolving Essence of Art and Architecture in Early Modern Europe, ed. Lorenzo Pericolo and Elisabeth Oy-Marra. London and Turnhout: Harvey Miller/Brepols, 2019, 261-73.

- “Luke, Lena, and the Chiaroscuro of the Sacred: Caravaggio’s Madonna di Loreto,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 71-72 (2019): 162-77.

- Co-organizer, with Lorenzo Pericolo, Baroque to Neo-Baroque: Curves of an Art Historical Concept, international conference jointly sponsored by the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz/Max-Planck-Institut and the Bibliotheca Hertziana/Max-Planck-Institut für Kunstgeschichte, Florence, June 3-5, 2019.

- “Sculpture, Rupture, and the Baroque,” in After Trent: Rethinking Global Art around 1600, ed. Jesse Locker. New York: Routledge, 2018, 33-46.

- “Drapery,” in Textile Terms: A Glossary, ed. Tristan Weddigen et al. Textile Studies 0. Berlin: Edition Imorde, 2017, 80-84.

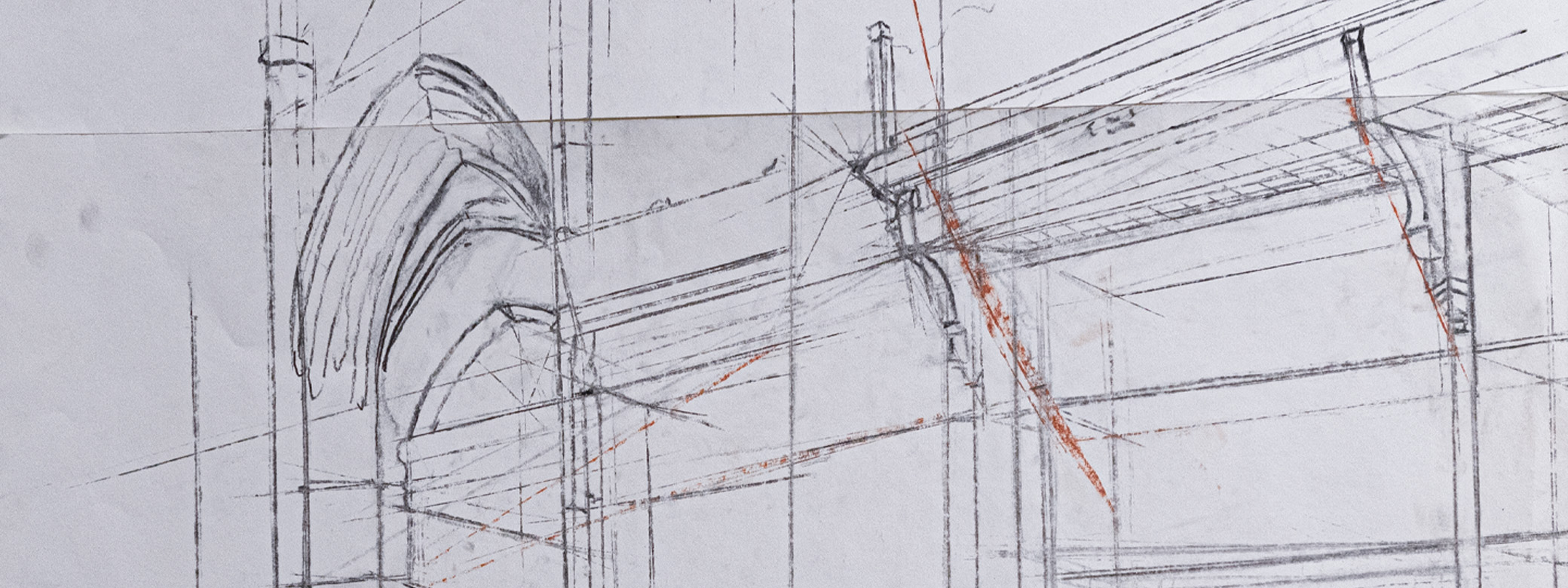

- Estelle Lingo. Mochi's Edge and Bernini's Baroque. London and Turnhout: Harvey Miller/Brepols, 2017.

- Estelle Lingo. “Impossible Apostles: Francesco Mochi’s Sts. Peter and Paul for S. Paolo fuori le Mura,” in Tradition and Innovation: Critical Perspectives on Early Modern Roman Sculpture, ed. Anthony Colantuono and Steven Ostrow. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2014, 63-85.

- Estelle Lingo. “Putting a finger on it: Bellori and Sculpture Criticism,” in Bellori’s Terminology: Tradition, Construction, and Usage in his Lives and Art Literature in the Early Modern Period, ed. Elisabeth Oy-Marra. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2014, 173-86.

- Estelle Lingo. “Looking Back: Mochi and Borromini at S. Giovanni dei Fiorentini,” in Renaissance Studies in Honor of Joseph Connors, ed. Louis Waldman and Machtelt Israëls. 2 vols. Milan: Officina Libraria, 2013, 597-603.

- Estelle Lingo. “Francesco Mochi’s Balancing Act and the Prehistory of Bernini’s Four Rivers Fountain,” in Matters of Weight: Force, Gravity and Aesthetics in the Early Modern Period, ed. David Kim. Berlin: Edition Imorde, 2013, 129-50.

- Estelle Lingo. “Sculptural Novelty and the Florentine Tradition: Francesco Mochi’s Orvieto Annunciation,” in Novità—das “Neue” in der Kunst um 1600: Theorien, Mythen, Praktiken, ed. Ulrich Pfisterer and Gabriele Wimböck. Berlin: Diaphanes, 2011, 211-37.

- Estelle Lingo. “Beyond the Fold: Drapery in Seventeenth-Century Sculptural Practice and Criticism,” in Unfolding the Textile Medium in Early Modern Art and Literature, ed. Tristan Weddigen. Textile Studies, vol. 3. Berlin: Edition Imorde/Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2011, 121-29.

- Estelle Lingo. “Mochi’s Edge,” Oxford Art Journal 32 (2009): 1-16.

- Estelle Lingo. François Duquesnoy and the Greek Ideal. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Estelle Lingo. “The Greek Manner and a Christian Canon: François Duquesnoy’s Saint Susanna,” Art Bulletin 84 (March 2002): 65-93.

- Estelle Lingo. “The Evolution of Michelangelo’s Magnifici Tomb: Program versus Process in the Iconography of the Medici Chapel,” Artibus et Historiae 35 (1997): 91-100.

Research Advised

- Vallah, Or. “(Dis)ability and the Making of the Early Modern Artist.” PhD diss., The University of Washington, 2025. ProQuest (28453).

- Kit Coty, "Maniera Etrusca: Gardens, Vernacular Landscape, and Regional Identity in Sixteenth Century Tuscia". University of Washington, 2023.

- Tori Champion. "Le pinceau à la main: The Intertwined Lives and Careers of Madeleine Françoise Basseporte and Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien." MA Thesis, University of Washington, 2021.

- Caroline Harvey. "Replications and Reconciliataions of the Borghese Sleeping Hermaphrodite." MA Thesis, University of Washington, 2020.

- Karen Lark. "Bernini's Blessed Ludovica Albertoni: Drapery and the Permeability of the Body." MA Thesis, University of Washington, 2020.

- Krista Schoening. "Looking at Jacopo Ligozzi’s Daphne laureola in Three Ways." MA Thesis, University of Washington, 2019.

- Lane Eagles. "On Her Substance: Dress and Fecundity in Renaissance Painting." PhD Dissertation, University of Washington, 2019.

- Anna Wager. "Kindred Spirits: Communal Making and Religious Revival in Arts and Crafts Movements, 1870-1920." PhD Dissertation, University of Washington, 2018.

- Barbara Budnick. "The Lay of the Land: English Landscape Themes in Early Modern Painting in England." PhD Dissertation, University of Washington, 2017.

- Jena Mayer. "Francesco Furini: 'Paintings of Exceeding Beauty' in Seicento Florence." MA Thesis, University of Washington, 2016.

- Victoria Wilmes. "The Chapel of the Madonna della Strada: A Case Study of Post-Tridentine Painting in Rome." MA Thesis, University of Washington, 2012.

-

Spring 2025

Winter 2025

Autumn 2024

Winter 2024

Autumn 2023

Winter 2023

-